Post-China Post 5

I spent five years in China. I am no longer expecting to return.

While it seems like barriers to travel – these and a hundred signs say that the country is turning inwards, preparing for some other surprise – will keep casual travellers away for another two years, something more has been broken in me and people like me. One of the strangest inflections of the pandemic for me has been to realize that the virus, however it became a world-plague, likely came from a rainforest in which I briefly stayed. The Mojiang mine, whatever its place in the calamity, was just a few kilometres from where I was working.

Flashing images of the biology of that region form the strongest memories.

For instance, I remember watching the bats flying out of a cave in Thailand.

This was in 2016, at the end of the summer, in north-central Thailand near the border with Laos, not quite two days’ drive from Yunnan. I was on a day tour with a group that the owners of my small hotel had badgered me into joining. I was tired, having come from Yunnan through Laos in a single day, walking across the strange border from the fortified Chinese gateway through a no-man’s jungle with shaggy vines and a vacant temple to reach the Laotian side. Their rat-coloured bivouac was made of sticky planks and run by cops with gold teeth and gold chains. They smilingly asked for the visa fee, wrote in my passport with a biro over their stamp and handed over a small pink slip. After that, a crowd of kids and older men rushed me to offer their taxis and moped rides. The grey-green leaves whipped about behind their heads over bright mud on a serpentine road.

First, I pushed these men away. There were two other confused foreigners – a couple with backpacks – and I went to them and we joined up quickly to arrange a ride across the country to the Thai border, crossing again on foot, this time a bridge over a river.

The bats in Thailand, a few days later. They were coming from a blade-shaped gap in the rocks near the crest of the hill – from high up, not from the ground-level entrance we had just explored as a group, with its diffuse funk of guano and fungus and its weird light beams. In there, there had been a Buddha statue. We’d been able to hear them, probably as they were waking and refreshing their wings for their night out on the canopy.

We had looked up to see them, looking down at us in there. Now they were awake.

We were watching them pass by. The sounds they made collected into a snickering thing that teased at being meaningful. The wings made whirring and buzzing phrases. It seemed throughout as if the sound were just about to become an ordered flow, like a guttering tap you expect to find its purpose and release a proper stream – but it didn’t. It never made sense. It oscillated at random as the column thickened and tapered away. Their squeaking existed somewhere behind the scene, in a vanishing state, coming at us from far away. The buzzing and the black shapes flickering past the sunset – the Thai sunset, which was pink – would have made you think of TV static, if you were old enough to remember.

One of strangest things: the static noise on the TV, some of it, is from the cosmic microwave background. It’s radiation from the start of the universe.

Since all this started, with diminishing ability to sleep, staying in an endless chain of hotels, spare rooms at friends’ places, AirBnB spaces in Europe and sublet apartments that smelled like other people, I’ve come to listen to scientific tales at night. Astrophysics and astronomy help to curb the vigil that seems to arrive by itself and force nightlong contemplation of the event that has wrecked so many things. It is interesting to be reminded of humanizing embarrassments in it. How Fred Hoyle, the English astronomer who named the Big Bang, did so in rejecting the theory. He argued that the universe maintained a Steady State, particles and systems manifesting to compensate for entropy and the loss of our energy. He was looking for stability in what he measured, in the universe. He also wrote science fiction. One novel concerns a giant sentient cloud of gas that blocks out our sun. We eventually figure out how to communicate with the cloud, which explains that it and its kind have ‘always existed’. So a giant talking cloud of gas repudiates the Big Bang, in its own way.

Now most of them accept the Big Bang in some form; we are multifarious things that came out of a singularity. It keeps expanding at faster rates, and we just have to accept it.

The coil of bats kept sliding out of the cave. It felt its way deliberately down to the forest canopy like a rope lowered into some green water. The scene had the look of a ritual manoeuvre, like something impossible to change as well as hard to understand. What could you do to influence it? You might feel inspired… but could just as well feel impotent before it, to see birds migrating, locusts rolling in to absorb entire fields, crabs covering beaches so you cannot walk there. A jellyfish bloom: what could you do about that?

Eat them. Maybe.

What would the first humans to see those bats have thought of them and their overhead sounds on strange wavelengths? Harvesting them to eat would probably have been easy, yet they probably left them alone, telling each other it would be bad luck to do so.

On the Thai ground, on a patch between our little tour coach and the cave entrance, the Thai guide was repeating her spiel about the bats as they continued to flow from the opening.

How many tons of bugs did we think they would eat, during the night?

How old did we think the cave was?

She laughed automatically at our inaccurate guesses. For each stage of the tour, she had a little set of one-liners. She had noticed at some point that I wasn’t laughing at these, and had started to ask me if I was enjoying myself. Prior to the bats, I had not been much interested.

There was a small temple by the cave and, she said, a couple of monks lived nearby. They tended to the temple and to the Buddha shrines inside the caves, but they were not around. As we climbed back into the coach to drive on to the next location of our tour, the bats were still flying out, in smaller numbers. Our arrival had been timed to the sunset to catch their appearance at its heaviest flow.

***

The more I read now, the more I think about it, reflect on my time in China, the more I am convinced the outbreak of the virus came from – or because of the existence of – the Institute of Virology in Wuhan or one of the many other labs there.

The denials, the restrictions on data that began in that city have their own familiar and organic pattern – denials from the top in a system used to assigning truth to things in a visible and blatant way. Too many indicators cluster about the lab and its sample collecting in the tropical south. The likely reservoir source is agreed to be horseshoe bats in Southeast Asia – a different part of the Chinese universe. How did it get from those caves to the north?

The lab’s databanks are taken offline. The research withheld. The moves to sever communication look so obvious: they have a smell of absurdity that you recognize, having lived there. Where authority can deem a thing to exist today and not tomorrow. Where the leader has a status connected to the infinite, to distant organizing principles that shouldn’t ever worry you.

Now that some decent reporters have gone to work on the problem, it starts to seem clear: something about the lab, something about the bat sampling, something looks and smells wrong. Many questions arise about how work in caves in Yunnan was done by the lab workers, where the lab’s money came from and how risky collaborations across the world of the virologists were organized. But this being China, there is no chance of us reaching the end of the rope. The most needed facts and events will be lost in the noise. As with those little games that try to help us apprehend the scale of the solar system and the galaxy and universe, reminders of the scale of China are needed from time to time. Reading articles by people who never explored it, elements seem missing, like we are looking at a map with municipal lines and no topography. The south, Yunnan and the jungles in neighbouring countries, that was where the bats lived that almost certainly incubated the virus – where the virus almost certainly ‘came from’. Far from Wuhan. In 2003, SARS-CoV-1 spread from Guangdong, part of the tropical southern band like Yunnan and a place known for the eating of wild and exotic animals.

It moved fast, not as fast as ours, out to twenty-nine countries.

The deaths were concentrated in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore. One infection in Ireland.

How did SARS-CoV-2 project from a bat’s intestine in the jungle to the bloom across the planet? Through Wuhan.

If we believe that it had nothing to do with human interference – or human interference of the hunting and trapping kind – then we must believe it travelled overland somehow without clustering or killing anyone, before landing in a city full of labs to show its potential. A city with one lab holding the largest collection of coronavirus cultures ever swabbed from bats, an undertaking that was pumped with resources because of the dangerousness of the 2003 outbreak of SARS-CoV-1.

The absurdity of all of this should be noticed more.

Even if none of it looks connected, and you think the virus made it to Wuhan and into humans through an intermediary species from the wildlife trade that no-one has been able to trace, despite tens of thousands of new samples collected by authorities (SARS-CoV-1’s probable intermediary, the civet cat, and origin point in horseshoe bats in Yunnan, were discovered within months), consider this: Yunnan and Wuhan are completely different in their character as well as their location, a jungle and a major transport hub in the middle of the population-dense part of the country, separated by multiple megacities and hundreds of millions of criss-crossing lines of informal and formal exchange.

How did it get there?

We all want to think past this. When considering the future, consider the flow from Wuhan’s ports: 7 million people left in January. Tens of thousands on international flights. In its timeline, New York Times notes that, by the time Beijing and the WHO began to speak in accord on the severity of the problem, ‘Outbreaks were already growing in over 30 cities across 26 countries, most seeded by travellers from Wuhan.’

Time works differently in China. The acceleration of change isn’t easy to grasp. In the year before the outbreak, the number of passport holders was on course to double from 10%. Five years before that, it was at 4%. The government sought to increase the number of citizens eligible to travel. It has now shut down most international travel, giving itself as much time as it needs to remove the virus at home. Yet it was slow, by Chinese standards, very slow to stop the outward flow of people in the beginning.

The drift of events has an organic and irresistible tempo. We will be told to keep the masks on – until it’s time to scan our faces. We are being ushered through the gates into a future shaped by disasters like this one.

Chinese Passport holders to double by 2020 fuelling overseas travel

Chinese passport fees dropped from 160 yuan to 120 yuan since

July 1, a 25% reduction coinciding with the summer break that’s

likely to fuel further interest in travel. There’s 240 million Chinese

passport holders projected by next year, doubling 2019 numbers.

… Data shows that only about one-tenth of China’s 1.4 billion people

hold passports, a relatively small figure. However, it is reported that

Chinese travellers spent more than 120 billion U.S. dollars overseas

last year, surpassing other countries.

CGTN News, 10 July 2019

***

I did not spend a long time in the forest.

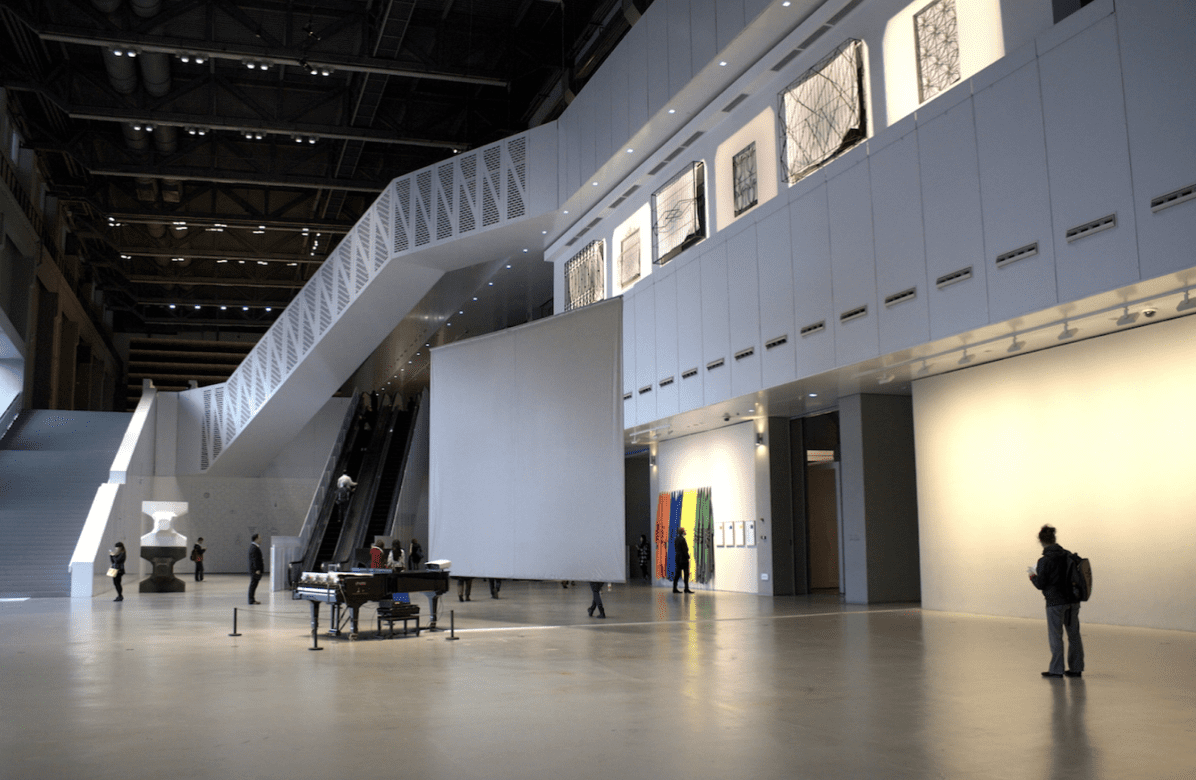

The whole adventure was done on a whim. I had been in one of the big new galleries in Shanghai, the ‘Power Station of Art’, intended to rival the Tate Modern.

Walking with my girlfriend I was faint and impressionable after drifting through the magnified light beams falling through the architecture like wind through the rigging of a ship … and passing over art objects with no water to drink.

In a corner off the main corridor we found a strange, busy little set up, like a popup shop.

This was the volunteer organization, showcasing its charitable work across the country, outreach work in poor and ethnic communities. Places where the adults had disappeared from the village in search of urban work, leaving kids and grandparents. These neglected places could be found in the peripheries of poorer industrialized places and in forests, up mountains, down valleys.

There was much from Yunnan. Ethnic children and their teachers in bright branded T-shirts. Samples of grains and tea grown in these places. In one glass case was a ‘dancing plant’ and a small Bluetooth speaker: it was a miniscule sprout that did seem to shake when they played tracks through the speaker at ten-minute intervals. The little leaves were surrounded by laughing faces from the Shanghai schoolkids brought there by parents or teachers somehow involved with the group.

My girlfriend nodding, I added my name to their list for the summer session. They seemed to have a clear enough vision. They had an app of their own.

It was to be a door into strangeness.

First, a month later, I was sent by train to live in a barren, bleak township in Jiangxi where I entertained the children of carpet-factory workers, little screaming people who bumped each other and never sat still. The skittishness, we were told, might be because their parents mostly left them in front of televisions, or unsupervised with each other. We were there to watch over them and play with them, and any ‘English lesson’ dissolved fast as they ran out of the learning area.

There was an exhibition space showing the different kinds of carpet that the factory made. There was a factory floor I was not shown. In the sales office people sat sighing or sleeping as fans turned and flies explored the ceiling. I guessed it was a mostly dead enterprise kept half-awake on government support. All around it were empty businesses, a ghost pig farm, a shell factory with no gates that I went into with the Chinese student who was my fellow volunteer, both of us joking about the sinister terrain and taking photos of the gaping entrances and rooms and debris.

After a week I was flown down to Yunnan. I and some others from the city would serve as distractions for local kids – yet this time the offspring of very different kinds of people. They were tribal, mountain people from Xishuanbanna; their children had dark faces, intense voices, more deliberate and vital movements. This is a place whose name retrieves images automatically for northerners. It is the jungle of China, one of the biggest in Asia. Its valleys and peaks, its giant rainforest, its wild biomass, its tribes, all make Xishuanbanna ‘very famous’ they will say – appropriate that in the country’s most ethnically diverse place is to be found the most biodiversity.

These images are the way I remember it:

The arrival. I was on my own. Healthy trees leaned in towards the glass wall at the arrivals terminal.

The drive. The driver trying to communicate. Playing a song whose refrain was ‘Xishuanbanna’ with the word timed to lift from the car as we rose into a mood-breaking valley opening down into the earth and extending towards the sun, full of dancing leaves.

The driver. Asking me if I knew about the cannibals. No, I didn’t. Yes! We were many cannibal before. Not now! Don’t worry.

The length of the drive, which went on for hours on a road almost always rising, through a world of leaves. Wild bamboo on the left and banana plantations and rice on the right.

Turning into the concrete driveway of the school.

The head of the cow. On the front yard of the school a small man in a rice straw hat was blowtorching the blackened head of a cow. The kids playing behind him. The hooves and torso and parts were laid out in a row. This cow is for you, I was told.

Where I stayed. In a dorm the kids used during the year, on a thin bed. Sad smells. Enamel of the bedframes looking gnawed on and everything scratched as if by fingernails. As I was touring it all with a girl from Shanghai, a fellow volunteer, kids followed giggling.

The meals. With the teachers, luxuriating in their free time for summer. They lived near and used the school as their restaurant. The eating space on the floor of a corrugated open lean-to that leaned against the mountain.

The cow. Pieces of it came to me in bowls through the week.

The school principal. Like XI Jinping, like various bosses and fathers, he sat in an assigned place and presented a rigid posture and a fixed expression.

The baijiu. The teachers likely made it or knew whoever did, something with fruit was done to it and it was brutal. They drank it at lunch and dinner. They enjoyed toasts and I joined them. The principal might smile as they laughed red-faced. He led the most important toasts, they would stop laughing.

I had the feeling he was watching me.

The man in the straw hat. He had killed the cow (my welcome cow) himself and done all the work.

He was a veteran of the war with Vietnam. I probably said he looked Vietnamese and had it translated. Probably everybody laughed.

My fuck-up. Once, too drunk from the toasts I turned to the Shanghainese volunteer girl in front of the company and asked her to my ‘room’ where I had condoms, likely no-one understood but she was grievously embarrassed. I got a quiet call from the charity’s boss asking me to stick to beer.

The butterflies. Playing badminton in the yard out front with a girl, one of the Dai children making up most of the cohort, I watched the small yellow feathered dart we were hitting with the rackets go up in the air – at the top of the arc, yellow butterflies would rise toward it, trying to mate with it.

The butterflies in the forest. I would walk up the hill. Kids on mopeds would slow down to offer me a ride. Amazed at my double-strangeness: my pale neck and arms in the woods and my walking there.

I was listening to podcasts. Once I had to go in the forest. My guts weren’t working. The butterflies came and landed on what I left there and covered it with themselves before I was back out on the road.

The Dai. Sometimes it was explained to me how the tribal people organized things. One of the Shanghai volunteers told me, when a student was nearby, She is a Dai girl. Do you know, she doesn’t have a name? Sometimes they are just called Dai girl.

I said, Does she like not having a name? They spoke. They both laughed. She says she doesn’t mind.

A Norwegian anthropologist came, he had been resident there before, doing field work in the community. He was good looking and tall and enjoyed lowering himself onto the tiny plastic school and speaking Chinese well and showing how he loved the food. I found him too woke. We tried to be friends, going into the nearest town for drinks. At an ATM, I saw a gecko run across the screen from the shadows and eat a moth that had been lured in by the light of the screen.

In the shower block, the collective one normally used by students during the year, I was trying to shower one day. I looked around the shoulder-high cubicle and saw a small boy peeing into the drain alongside. In my room, kittens found their way onto the pillow and shat there.

I left a day early for Thailand, set to meet my girlfriend in Bangkok.

The principal of the jungle school. My bosses in Shanghai, the president. The Qianlong Emperor in his portraits. They all presented the imperturbable face and maintained the infallible posture.

***

How often are misguided words or decisions from the leader stamped into the skin of Chinese things?

My English friend James, who lives in a dour city near Shanghai with his wife and son, who nourishes a lively resentment against his father to this day, made a chatty game together with me, years ago.

We had met at a start-up in Shanghai concocted by a rich investor. The investor had based the start-up on his insights into his daughter’s SATs. Glancing at the tests, making a connection between them and ‘free’ social networks, the investor believed that he could employ us, a few ‘qualified guys’ who would then hire and manage freelancers online to mass-produce tens of thousands of test passages and questions. Then we would open these tests for free, monetizing the data and the services later, building some kind of social stratum on top to emulate Facebook. Facebook’s virulence and data made the investor salivate.

As he unfolded the idea in front of us and his local team of underlings – a small henchman, many graduate Chinese girls – he would raise his squeaking voice at this potential unicorn rise. ‘We could be the biggest test company in the world … ten billion dollars.’ The early meetings were in big glassy boardrooms, the girls clapping at the end. Us trying to clap with irony.

The hubris and absurdity of it was most evident to James, who fussed and moaned from the beginning about how the tests were being made. James who ground his teeth describing his own father spat most rancorously about the billionaire. He could see how it all would go.

The boss was rich enough to have offices for his main company – an investment fund and corporate finance consultancy – in one of the main skyscrapers in Pudong, the location of the Shanghai skyline. That skyline has the Pearl TV tower at the centre of the silhouette, like eyes impaled on chopsticks.

We would look out the window directly into the roundabout over which the tower rose.

James, who would work from home and come to Shanghai for meetings that maddened him (‘They have no idea what they are doing. None. It’s a fucking total waste of time.’) quit after two months and went back to working for small money as a writer and in high schools.

To the billionaire, it was incomprehensible. They had given James such a great deal. Because James had a kid, he could work from home. ;Work from home!; This was quite a prize. And there were the stock options we were to be offered, just like Facebook.

They called the start-up Quizbook. I stayed working there for another year fulltime, then moving to part time for another year of botched attempts to imitate, steal or emulate complicated material. James had been right. It went nowhere and its vacuousness seems obvious now.

But, all along, the vessel drifted towards the rocks because: the billionaire had had the idea; he was a billionaire; he was the boss; he had to be right. Often if you tried to explain a pedagogical concept in a meeting, you would be interrupted, mostly ignored; it wasn’t your fault that you didn’t know not to do that, the moment was passed over. The meeting would end. Then the idea would come back later, now it was their idea, it had always been their plan – the boss and his familiar, a small man with vacant eyes and a quiet voice who was always near his master, or slithering into the brown smoking chamber to sit over the ashtray, the only the thing on the table in there. Just outside the smoking room door, in the corridor, was a company group photo on a decorative wooden stand, all the finance team and the billionaire posing with George W. Bush.

There was the appropriating of work – we were asked many times how we could hire people to simply rewrite or recombine existing content – and the denials of what was happening, of the nature of what they were doing (making a rip-off), even more absurd. ‘We understand IP, of course we respect it!’ And the methods; James told me that, before I arrived, another foreigner had been there a short time. He was a writer so they asked him to write a ‘passage’, or something akin to the extracts of prose to which questions are applied in the verbal section of the test.

To do this, they brought him a laptop, asked him to sit and write – and one of the girls sat behind with a timer and timed him. This, they reasoned, would tell them how to plan making thousands of pieces of original English prose.

The billionaire, who called himself ‘John’ Wang, would summon me sometimes for chats to build rapport, or to try to trace the outline of some problem – which was never, of course, derived from his own chronically flawed idea. Which possibility never arose.

Explaining the world of finance, and China, and the Communist Party, he once surprised me. He was of the Tiananmen generation, he said. He had not completed study in Beijing. He’d graduated as a doctor in the States and come back for the boom in the 90s. He showed a little more of his feelings. The CCP liked nothing more than to crush people, he said.

‘鲁科,’ he said, ‘the world is evil. There is almost no one you can find with a lot of money who hasn’t done something evil to get it.’

‘What about you John? Have you done anything evil?’

A pause of odd length. And, totally straight faced –

‘No.’

James found this particularly hilarious in a way I didn’t yet understand. Staying friends with James, we messaged on WeChat every day for years. Strange patterns came through this mass-messaging friendship. I did light freelance work with propaganda papers and projects and, reading the English-language output from the party, began to learn a feel for the absurdity. Friends also worked in these places and would assemble stories about stories.

About untruths uttered by authority that seemed so extravagant they belonged in a fairy tale.

The wolf forever panting in the old lady’s nightdress.

The little chat game we had was about denial.

Implausible denials in an escalating order.

- I was in a hotel the other night. Drank a lot. With someone. Wife knows. Someone took a photo. Shared it with wife.

- Say you weren’t there. You don’t stay at hotels.

- Right. I don’t actually sleep.

- You never sleep.

- There are no hotels here anyway.

- Chinese women don’t sleep with foreign men. It’s a myth.

- There are no hotels accepting foreigners. It’s a myth.

- The city has no hotels. Those are not hotels.

- It wasn’t me in the photo. There are no photos of me.

- Right, there are no cameras in phones. They don’t work.

China has no tropical south, a thousand miles from the Yangtze plain. China has no caves.

China has very few laboratories. The US has far more.

There are no bats in the caves. The last two years didn’t happen. The path to 2049 is glorious.