Post-China Post 1

We now begin a series of posts, one a fortnight, from a young Irish citizen-journalist and poet recently back from China where he has lived for the past five years. He awaits his return.

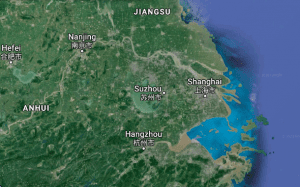

I have been back in Ireland for about five weeks. I’m Irish, but I lived in China for about five years, in Shanghai and Suzhou. Suzhou is the capital of Jiangsu. Jiangsu is a province adjacent to Shanghai. Suzhou has ten million people. Shanghai has about twenty-five. No one would tell you that Jiangsu people sound like the Shanghainese, just a hundred kilometers away.

They will tell you that Shanghai has its own language. But Shanghai has no province. It is one of the ‘four special municipalities’. Beijing, Chongqing and Tianjin are the others. The only one I have not visited is Tianjin, which has about fifteen.

zhíxiáshì

直辖市

‘Special municipalities’

Looking at these terms now, I know how they would sound only from the pinyin (roman letters) beside the Chinese. I can hear them accurately as I read the pinyin. According to the national curriculum, Chinese children should learn 3500 characters by the end of primary school (four years). That is enough for an adult too, for everyday speaking. There are 85,000 characters in the whole language. I recognize only a few. Knowing how it sounds and feels and flicking a few switches in the heads of others is all I have got.

Shanghai of course, isn’t really China. When a friend criticized me for remaining in Shanghai (not just in Shanghai, but almost entirely in Xuhui and Changning and Jing’an, the three most western of the sixteen districts), I said I had lived in Suzhou almost a year, and he laughed at me. Suzhou is an hour’s train ride from Shanghai. The ticket is forty yuan, about five euro. I can book one now, on my phone, for tomorrow. The schedule is back to normal.

Suzhou is one of the ‘heavens on earth’ in the Yangtze delta. The other is Hanghzou. Everyone knows that they are beautiful. Heaven is in the sky, Hangzhou and Suzhou are on the earth. Ask someone to name one of Hangzhou’s heavenly things and you’ll hear them say the Xi Hu, the West Lake, a manmade water feature from the Song, or the Tang (or even the Sui?), with pathways alongside, and stone walks through it, normally very busy in the Spring, but not this year.

In Suzhou, it would be the gardens and the canals. They keep these latter flowing and busy with ornamental activity, including cormorant fishing and singing melancholic boat women that proceed beneath the historical snack street.

Suzhou, which will be connected to the Shanghai subway by 2023, has sometimes worked as a destination for artists, who required a location near, but not inside, the special municipality of twenty-five million. Who want to be within commercial distance of Shanghai, with its sixteen districts (I’ve been to all of them except Chongming), but not inside it. Shanghai, with its 676 kilometers of subway, its 413 subway stations, its wealthy people (well-off first, then wealthy – let’s say hyper-rich, by now), collectors and middle-classes, who need their visits to pretty satellites and boutique destination cities as they need their malls and their luxury items. In the Yangtze delta, many of these getaway places are ‘water-towns’ with miniature canals that are connected to the grand canal, which connects to the north, to Tianjin and the Yellow River and Beijing.

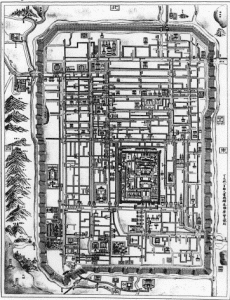

The old part of Suzhou is beautiful in part because it used to be a real Chinese municipality (by which I mean, interior, canal-fed, ancient, sitting on a civilizational seam of middens, shattered pots and iron chits going down to a great depth, most of it unlikely to ever be excavated). It has a grid shape, a rectangle inside a wide moat, which I’ve walked over in the rain, feeling feeble in my heart, trying to find an apartment near the beautiful part near the water. (The moat is more serious looking than the canal barrier around Kyoto, which I’ve also walked over, feeling lighthearted and eager on a short trip in 2018. Kyoto was modeled on Chang’an. There are always gates, walls, a grid, main streets and alleyways in these places.)

In Suzhou I went into an alleyway near the moat, through a circular door, with an agent who brought me to view an old alley-house. It was inside the old city moat and so it was overpriced, needing an up-front cash investment. As the rain fell and I observed cats that looked like they’d recently given birth, and old men scratching their asses and watching us, the agent shouted through his phone to the owner, who informed him that foreigners were not allowed to take the lease.

Old Suzhou is inside a modern belt, which is inside an industrial and heavy transport zone, whose orbital edges blend into those of Shanghai, Suzhou forming a central hub in the Yangtze River Delta region, with Wuxi (3.5 million), Changzhou (4.5 million), Nantong (7 million), Huzhou (2.8), Jiaxing (4.5) and Hangzhou (10) encircling. Ningbo, connected to Jiaxing by the Hangzhou Bay Bridge, isn’t far away. Ningbo has 8. It is apparently nice enough. A friend worked there, something to do with the port. Not much to do at night. I once interviewed for a job in Ningbo, to write website copy for a company making ‘environmentally aware’ wooden toys for Europe.

In Suzhou I knew even less than I ever knew what I was doing in Shanghai.

It was 2017. I had broken up, my girlfriend gone back to her home country. I was approached online and asked if I would try doing the marketing for a robotics company. Robots that clean your floor and windows, always bumping into walls.

I stayed in an English guy’s empty flat, for the first few months, then hotels. The structure of the city was strange, and my work was far away from the northern lakeshore, where the foreigners were. I never found an apartment or a lease.

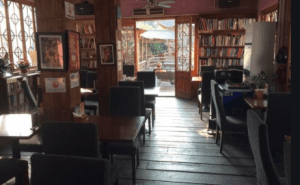

In the evening I would gravitate to a place I loved, a place near Shiquan Jie and Gongyuan street called the Bookworm. Inside an entire canalside house, a gabled wooden house from at least the Qing dynasty, there was a small bar and two stories with shadowy stairs. There were bookshelves and tables, the shelf contents formed from the detritus of personal collections left by foreigners passing through China, and tables and chairs of different sizes. The books were for reading there, maybe some of them for buying – or borrowing? Or taking? It wasn’t very clear.

There was a lethargic cat and sometimes performances. A patio in the front always had a promising glow under a few lanterns. The poets and artists (Chinese ones) would be sitting around on that patio when significant gatherings took place. There were readings, bilingual ones, and enough musical gear for small gigs.

I organized a reading. I read with a translator friend from Hangzhou whom I’d met in a wine store in Shanghai. His English name was (and still is) Yates, after WB.

For the tiny audience, mostly older chinese writers there to read their own stuff, Yates read a translation from a beat writer, or part of a Leonard Cohen book he’d done that year. Everything was odd and incongruous. An old poet with no English at all signaled to me after my own reading by holding up a can of Guinness. He was small and apparently aging in front of your eyes. Yates told me after that he was the most famous guy there. The old poet was insistent about how his stuff be read. He couldn’t read it himself. He asked via whisper that his poem be read twice, both in English and in Chinese, by his collaborator. She was a pretty girl, if I remember right, who might have been his translator or his carer or a daughter or all of these things. She helped him to walk around. His poem was a barrage. I counted three or four extreme emotions packed among the images, action words, abstractions that seemed clear for a second and flashed away. Then it was done. I had little idea what it was about. He grinned at me again. Yates said that that it had been a typical style, ‘now a little out of fashion’. Yates went for a smoke and to talk to the old guy, being helped out under the lanterns.

Yates can be theatrical. His English is elaborate and fast. But his accent is undentable Chinese, a vaudeville impersonator of long ago with blaring tones, weird vernacular style and zero-latency understanding shaped by the internet, work and reading. He manages sales teams at a management software company – I think. I have never understood the job. He squawks when he is inspired with an insight and endangers his cigarette-affected teeth so they seem ready to be fired out towards you. His vocal anatomy in a permanent strain, me smoking out of a habit you can acquire in Chinese friendships, we would go along the green streets in Hangzhou, past canals, always conscious of the West Lake’s location. Spitting and bitching about Alibaba. But using words with precision.

Not noticing that it had started to rain on his glasses, because he was busy with talking.

Most evenings at the Suzhou Bookworm there were no events. I would sit there and work or read. There was a piano and the retired American with his grey moustache (Tom? Henry?) would pass by and noodle on it. I loved being aware of the bats that moved in the air over the narrow waterway behind the back wall, as Tom or Henry played. If you could hear a sound it might have been their wing material flapping. At the back of your mind, maybe the needles of their clicks as they picked bugs from black alleyway air. Looking through the wooden shutters they could be seen inside the little shadowy space, going in and out of the moon and the streetlamp light. Bats apparently represent happiness and joy.

‘Five bats together represent the ‘Five Blessings’ (wufu 五福): long life, wealth, health, love of virtue and a peaceful death.’

The little waterway there connected to another canal fragment that went parallel along the whole of Shiquan Jie. Shiquan Jie contained attractive old-city dimensions, shopfronts with restored details and luxury traditional crafts, stone semicircle bridges that led off the street over the discrete canalway. It had some expensive boutique hotels and normal restaurants – and, very weirdly, towards the northernmost end, many late-night hooker bars, a hidden upstairs lesbian bar and a dive bar called the Drunken Clam. Most of which I went to once. The clam which I went to very often. The hookers and the clam are closed. Tom or Henry would go to these too. I would leave the Bookworm with him still sat there, and settle into some other bar – to turn around and find him there already, halfway through a drink. Suzhou was small like that. At the end of my year there I read a poem onstage about my ex in one of our favorite places, Locke Pub, named after John Locke, in an underground mall attached to a metro station. Tom or Henry played the keyboard. I felt happy with my own material for once.

It was Henry. He had a moustache, he was retired, and it was never clear what he had previously done.

Suzhou, which everyone knows is beautiful, contains many gardens. One of them is called The Humble Administrator’s garden, the largest old garden in the city. There is a story about it.

The Suzhou Bookworm was part of a family – there were also Beijing and Chengdu Bookworms. All are closed. The house that held the Suzhou worm has been demolished.

There is another tiny garden called the Master of Nets, which was built in the Southern Song (twelfth century). Shi Zhengzhi, the Deputy Civil Service Minister, was ‘inspired by the simple and solitary life of a Chinese fisherman,’ says Wikipedia.

The Humble Administrator was Wang Xiancheng, who lived in the Ming (sixteenth century). He wanted to retire in Suzhou and built up the garden over sixteen years. He wrote that ‘This is the way of ruling for an unsuccessful politician.’

At time of writing, China itself is closed. That life of five years duration is also over.

I decided to look up the meaning of five.

‘The number five is associated with both good luck and bad luck depending on context. Since 五 sounds similar to 无 (wú), which means ‘not’ or ‘without’ in Chinese, it can be viewed as bad luck.’

Yates, ten days ago, asking about the lockdown:

Y: I understand Irish people wouldn’t be able to sustain life for six hours without a proper injection of Guinness.

Yates’ icon in the app is now him wearing a mask. This struck me as odd. He always rejects the dynamic of the herd. He once sent me a video he took, driving around West Lake, shouting at another motorist through a miniature megaphone, calling the guy niubi for not dimming his lights.

Niubi means a ‘cow’s cunt’.

In January, he had been asking me to come down to help him deal with his liquor cabinet. He told me he’d get me through the checkpoints at his compound.

When had he gained this nervous attitude?

He wasn’t worried when he was simply working at home (that was in January, February, early March). His face in the icon was the same back then. But now he’s back at the office. There are no orders from overseas, and he’s worried. And his little icon face is frowning.

He tells me he thinks we are headed for a ‘full on cold war mode,’ and that he’s been ordering military rations and sacks of rice.

The virus isn’t real.

Shanghai wasn’t really China.

Maybe China isn’t real.

The flat earthers have their theory about Australia.

Have you been there? Can you believe in kangaroos?

‘Heaven is in the sky, Hangzhou and Suzhou are on earth.’

In Dublin, when I came back, I began to cycle about and found a café, closed but with the door a little bit ajar, where a Romanian woman was sitting. She made me a coffee. I came back each morning. I would sit at a table, away from the window. We would chat as she made her glass bead jewelry at another table, facing the large pane of glass. She had lived more than fifteen years in Ireland, had a daughter (the daughter now back in Romania with her grandmother). She had worked a lot of jobs. After a day or two she gave me coffee for free. She predicted that Bill Gates would be caught, arrested. She thought he should be arrested. Maybe the virus isn’t real. She didn’t know. She asked me if I thought the virus was real. ‘These rich fuckers,’ she said. ‘They want to control us. They can always do what they want.’

There’s a photo somewhere, Yates and myself and the old guy after the readings. I don’t know what server it is on, or on what hard drive, or if I have any of them, or if I can get anyone to put all my shit into storage, or if any of us can go back.

There are no bats. No one puts them into soup. No one drinks it. No one got sick. It’s all a myth. I’ve not been back home. Not for five weeks. I never left.