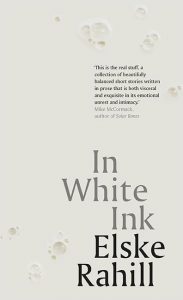

Rob Doyle on Elske Rahill’s In White Ink

Four years ago, in this same venue, I attended the launch of Elske Rahill’s debut novel, Between Dog and Wolf. I bought a copy, took it home, and read it over the next couple of days. When I was no more than a few pages in, my unease began to deepen in tandem with my fascination. Here, I realised, was a writer who would not spare my feelings – in other words, here was the very kind of writer I veer towards. Rahill’s novel plunged the reader without filter or protection into the loveless sex lives and interpersonal cruelties of students at loose in Dublin city. By the time I finished it, I was rattled. It was the same kind of feeling I had when first reading Michel Houellebecq, or Virginie Despentes, or JM Coetzee at his most merciless. The book left me feeling disturbed, bruised, violated – and grateful for it. It was clear to me that Between Dog and Wolf was the work of a hard, fierce new talent in fiction. I myself had only recently arrived back in the country, and was trying to find out which authors were worth reading, if there was anyone out there I had anything in common with. Elske Rahill couldn’t have known it, but reading her novel gave me the sense of discovering something like a kindred spirit, someone whose concerns and aesthetic I could recognise. The discovery was thrilling.

In her new book, In White Ink, Rahill has confidently expanded her fictional world, from the claustrophobic angst of young lust, into intimate territories of parenthood, maternity, family, and, in its manifold forms, love. In Rahill’s work, that last word, ‘love’, should not be understood in its usual, sentimental formulation. Rahill applies herself to the analysis of love like a vivisectionist. In her stories, we are frequently reminded that what often passes for love is mere transaction, or ideology. Love does not manifest where it is expected to, or where it is proclaimed most loudly. In one story, ‘Manners’, a character has the following reflection:

of love like a vivisectionist. In her stories, we are frequently reminded that what often passes for love is mere transaction, or ideology. Love does not manifest where it is expected to, or where it is proclaimed most loudly. In one story, ‘Manners’, a character has the following reflection:

‘There was no one who knew quite how to love anyone else.’

The sentence is planted quietly, unobtrusively in an unsuspecting paragraph, and it detonates with chilling effect. Elsewhere, however, it is not the absence of love, but the excess of it that destabilises. The birth of one woman’s daughter ‘had made her mad’, we are told, inciting ‘a tsunami of sentiment. She had been afraid of drowning in it; the love was too much.’ In the masterful stories that make up In White Ink, love wanes, or blossoms in the cracks between the lies we tell ourselves, or, in some cases, makes itself felt at the very extremes of human experience. In one of the collection’s most painful and admirable stories, titled ‘Bride’, we are taken into the stark consciousness of a woman and mother whose husband is guilty of heinous transgressions. Of their marriage, Rahill writes,

‘She was staying because she knew what it was to love, and because when she saw her husband’s chin tremble, his lip fold on the cusp of tears – ‘Look at me, Anne. Look at me. It’s me…’ – she was certain that she knew him, that she could love him, if she chose to, and that to love was a good thing.’

When I was invited to write an endorsement for this book, I wrote that Elske Rahill gazes long and hard into chambers of the heart where other writers fear to glance. I meant it: what makes her work dangerous and alive is the sense that Rahill could not deny her fanatical honesty even if she tried. Her gaze is unflinching, unblinking, unnerving. As a writer, she is like the man in her story titled ‘Tasteless’, who, at a wedding, ‘couldn’t bring himself to tell [the bride’s] father that she looked beautiful. He was afraid the lie would show in his face, and that was worse than saying nothing.’

I don’t want to give the impression that reading In White Ink is at all a deflating experience. It is true that Rahill’s native themes include shame, cruelty and selfishness, but the collection abounds with the thrills of fresh insight and intense intimacy, of discovering what remains when the illusions are cauterised away. The prose is limpid, graceful and frequently startling in its imagery. Rahill is a truth teller, and the ferocity and determination with which she pursues her quarry is what makes her fiction quiver with life. In Rahill’s books, to quote an adage from David Foster Wallace, the truth might set you free – but not until it’s finished with you.