Post-China Post 4

A billion balconies facing the sun; still, it means a final goodbye to wars and ideologies…

JG Ballard, Cocaine Nights, (1996)

XI Hails a Historic Free Trade Move / APEC summit endorses route to promote economic integration in Asia-Pacific

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit yesterday opened a route toward a vast free trade area in the region, host Xi Jinping said, calling it a historic step…

Besides accounting for more than fifty percent of the world’s gross domestic product, 21-member APEC also makes up nearly half of world trade and 40 percent of the Earth’s population. The APEC leaders also endorsed a proposal to work more closely to combat official corruption, Xi said.

Shanghai Daily, cover story, Wednesday 12 November 2014

Britain honors local cleaner with an MBE

A Shanghai woman who has worked as a cleaner at the British consulate General in the city for the past 28 years has been made a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE)…

Sexagenarian Wu, who works for cleaning subcontractor ISS Facility services, said winning the prestigious medal would encourage her to do her job as well as she possibly can and to strive to do even better.

‘Wu Ayi has been working diligently in the consulate for 28 years… and has created a neat and comfortable working environment,’ Brian Davidson, the incumbent consul general, posted on his Weibo account.

Shanghai Daily, Wednesday 3 December 2014

1. Foreign Commodities

In the Chinese home, the symbolic guardian of savings is a toad with three legs: his sole rear leg is supposed to indicate his lack of an asshole, meaning that when money is put into his mouth he cannot shit it out, so one’s money is safe inside the toad. Nowadays the toad is usually beside the cash register or POS, and has a plastic coin fixed halfway through the mouth-slot, but I think that it used to be iron and work like a piggy-bank.

The equivalent to the household toad on a national level is the lion; it is also equivalent in Shanghai to the symbols of ancient guardian gods. The lions are sitting outside the banks; not pacing or hunting, but guarding what’s already been got and roaring.

There is a lot of roaring in Shanghai; as I remember from Beirut, there was never the lack of the sound of someone building. Even when in an apparently silent room, waiting in a massage place for your masseuse, listening for it would turn up the tapping of a tool, or a faraway grinding saw, like someone shaking tinfoil on a sunny afternoon. On the street, the sounds were of cars, voices being screamed into phones, spitting and the storied bike bell.

The first real interview was with one of the English-language papers, the Global Times, which has both English and Chinese versions.

The GT reputation for impulsive demagoguery comes especially from the editorials, which in English are the work of the same visionary who directs the Chinese-language edition. Long before the present open strife with the US and the west, these broke pace with the usual stony insistence on ‘Harmony’ that one found in national-level commentary on international matters. His was the one Beijing hand that always poked aggressively at other nations.

The editor’s understanding of how this is to be done can seem strange. About ten years ago, after an opposition politician in Australia’s parliament made some remarks about Chinese companies’ acquisitiveness in Australia, the editor called for boycotts against the entire nation of Australia, to be applied until it apologized. [1]

[1] “A cocktail of conspiracies delivered daily”, John Garnaut, 18th of December, 2010 The Sydney Morning Herald.

As for the paper, I struggled a bit to find the address; I was still uncertain taking taxis. On the long avenue where the building was, I went to a café to prepare. It was humid outside, and I was sweating. I drank a smoothie and edited some articles I had printed, marking them in red.

As I entered the building and approached the elevator, I was carrying diligently my bag with annotated copies of the paper, as well as the printed stories. Many of the typos I found were contained in the editorials – I imagined that the powerful editor might be pleased that some new appointment had summoned the moxie to point out these errors for him.

I was after a copy-editing job, hoping to move on to writing. The entrance, on the fourteenth floor, had a necrotic feel, with a slob in a uniform asleep outside and piles of papers slumped around. Copies were spilling into the corridor space by the guard’s desk.

I called the number that I’d been given. Simultaneously two women saw me and walked towards me, speaking in Chinese and in English. I began saying my contact’s name. In all job-seeking meetings, the first person I met would be a woman, followed, if things went positively, by a man. The contact for the interview, a woman with whom I’d been in contact with before leaving for China, appeared and brought me to a computer among partitioned desks. I had been told about her by Jack. Following his advice, I had prepared some flattery, believing that making a friendly rapport with her would secure me a temporary future and validate my decision to come. I had thought through this occasion on the plane. She did not even accept a self-introduction. She gave no reaction when I mentioned Jack. She wouldn’t stop walking away. I didn’t get a look at her face. She sat me at a PC and told me to open a file inside a folder called ‘Test’. I would have three hours. The screen had a dry fingerload of snot wiped on a lower corner. It used a very old version of windows. In the folder was a file called ‘EnglishTEst’. A guy sitting across a partition from me sneezed miserably over the ensuing hours.

There were four stories inside. There was one about shares, which was dull, an ‘Opinion’ piece, which was boring – like almost all Chinese opinion pieces it was hardly an opinion at all, but a presentation of the most obvious reaction to a stimulus (an opinion piece mentioning ‘War’ in the headline, for instance, will conclude that peace is better option.)

Then there was a thing about nurses.

The increasing and aging population of China’s biggest mercantile center needs up-to-date care, but the influx of patients has not been met with a sufficient increase in the number of nurses. With a current doctor and nurse ratio of 1:1.09, Shanghai still lacks more than 40,000 nurses. It must acquire these by the end of 2015 to meet the standard proportion of 1:2, according to the Shanghai Nurse Association yesterday…

“To an urban center like Shanghai, crowded with so many medical resources, a total of 100,000 nurses may still be not enough in 2015,” said Ye Wenqin, the vice chairman of the SNA yesterday.

A Chinese article:

Some facts. A statement from an official, a load of numbers, another official.

A statement about growth.

Last, there was a travel piece, which was tender and strange. The author affable guy who was forthright in his desire to flee city life and to “sample the life of a fisherman.” He spoke of the near-medical necessity of leaving China’s cities sometimes – and I thought no shit – and of the shrinking areas outside then where one’s pleasure could be had in silence. The first line read, “I have fallen in love with an island.” The pleasures of the island, Weizhou, were described simply, one after the other. The simplicity of the island was its appeal; the small prices that he paid for each stage of the trip were brought forward as points of fascination in of themselves, and were as important as the natural beauty and bounty, which was the source of things to eat or to contemplate without much ensuing description. The island had no “multi-starred hotels,” he declared, and no KFC. To arrive there, the writer and his friend took a plane, then a boat, and then paid a fee to enter the island.

You need to pay another 90 yuan to be admitted to the island; however we also heard that there are some crafty people who come at late night on cargo ships and thus avoid paying.

In the story, they stay with a fisherman called Liu Quanliang. They rent boats, collect crabs from among the rocks on the shore, have crab porridge made for them by the fisherman’s wife. They go to the ‘Shell beach’, so -called because it is “sprinkled with shells after the tide goes out.” They find a catholic church, made by the French; Liu’s family are catholic.

In the evening, we went to the shell beach again. It was amazing to be in the water, watching the sky. Unlike in the city, light pollution did not trouble our view of the stars.

Determined to sample the fishing experience, they charter a small boat. The boat is a bit crap, but useable. They quickly find fish, but the delight that lingers for the writer is the smallness of the fee paid for this service.

The boat was small and old, and while we were a little dismayed at the condition our craft at first, life jackets were provided, and we soon cheered up as the fishing part got started. We were brought to a place far from shore and given fishing lines. That was all.

I got 6 fish in two hours, and Zhiyi got 4. For this excursion we paid just 150 yuan. Finally my friend and I returned home after five days, having spent only 450 yuan on accommodation. Other prices were also impressively low, a fact that may be due to the island not being known of as a tourist hotspot. For now, there is little commercial development. My final word of advice? Go to Weizhou before it gets expensive!

I made the necessary changes before the end of the long allotted time for the ‘Test’. It was the first of numerous occasions wherein the notion of a test would intrude on whatever roulette-style decision I had most recently made, with the actual test document almost invariably carrying the qualities of having been written by someone not qualified to do so.

The day ended without further conversation. I saved the file, moved away from the computer and towards the door. The carpets were bright red yet morbid from use. I already wanted to be on the Shell Beach. Some expats were joking loudly on the far side of the newsroom. One of them was a guy who did standup and knew Jack. These slogging journalists, obliged to inhale the smells up there, were supposed to become my confreres; but it wouldn’t happen, and I was starting to understand why. I would find work soon enough, but not in their arena. I was never informed about why I had not passed the test.

Someone told me before I came to Shanghai that a friend, with some ragged times behind him, had always said that “you can make anything in China except money.” That is one way to describe it. The mix of enterprise and emptiness that faces anybody headed out.

Many intimates warned me that the place was probably a kip; in support of this they lacked any images for it besides pollution and grind. But the research done before the emigration gamble had clarified that I would walk into some kind of job as through a swinging door; if the first gamble didn’t work, I could move to the next. It was that big. This was correct.

2. Copying,Collapsing

Official Accuses Dalai Lama of Profaning Tibetan Buddhism

A senior Tibetan official has criticized the Dalai Lama’s recent statement that the Tibetan tradition of reincarnation should cease with his death, saying that the religion and history must be respected. Padma Choling, chairman of the standing Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Regional People’s congress, said yesterday that the Dalai Lama was profaning Tibetan Buddhism by suggesting he will not be reincarnated when he dies.

Shanghai Daily, Tuesday 10 March 2015, [Xinhua]

Villages quickly vanishing from countryside

With China’s breakneck urbanization, people move to find jobs, leaving the elderly behind in an often bleak, lonely existence. Nearly 1 million villages disappeared in the recent decade, and many more are dwindling… For Pei Huayu, 61, life in Maijieping Village is reduced to the simplest of needs. Day after day, it is the same boring routine. On a sunny day, after having breakfast, Pei helps her husband go near the crumbling adobe wall to rest. Then she goes to farm the land while he suns himself. Qiao Tao, the husband, suffers Parkinson’s disease and is too sick to work. Their one and only entertainment is the black-and-white television… They have no visitors. The only time they see other people is every winter when villagers come back to sweep the tombs, or when old villagers are returned to be buried here…

Shanghai Daily, article by Qu Zhi, Wednesday 3 December 2014

Testing times for Disney

Officials said that workers have begun testing trains and signals on the new Disney line, an extension of line 11. The 9.15 kilometer route, which runs from Luoshan road to Disney… will open next Spring at the same time as the tourist attraction, said operator Shanghai Shentong Group.

Shanghai Daily, Wednesday 18 March 2015

One unpopular skyscraper in Lujiazui has a façade consisting of classical pillars on the outside of every floor, all the way to the top.

This is one easy instance to name. But there is mimicry everywhere; in every city great or small can be seen some sort of screwball imitation of the west, and old china is evoked with roleplay versions of the past. There are the Yuyuan ‘Gardens’ near the Shanghai Bund (not a set of gardens), the formaldehyde water towns around the city’s edges, the ‘Antique walking streets’ in every other city and whole-pseudo villages made Potemkinlike to satisfy village nostalgia as real villages die.

It is important to recall how successful China’s urbanization is. While most developing countries’ capitals generate huge unintended areas of settlement which then host ample crime and disease. The old European cities, unable to grow to meet the demand for housing, are full, and the price of land in their centers moves upwards. In Shanghai, the ascending price of land is matched by new construction, a pattern which mimics an earlier growth stage when ‘Shikumen’ tenements were thrown up to accommodate workers and their families escaping from inland famines.

At the same time, it should be said that the remarkable feat is paid for in how dolorous life in these cities can be, how perilous the ambitions behind the project are. Also, as happened during the Victorian-era growth spurt in Britain, large areas of the countryside in China are emptying, and villages dying.

As Mike Davis describes in his studies of urbanization, China’s planning and ambition have made its cities into more effective machines for growing settlement than others; unlike Mumbai or Cairo, there are no obvious slums. Instead there are hidden, vertically stacked groups of people living pressurized lives, contained within the forests of high rises made at speed Residential towers are often filled up with migrant workers on low pay, helping to make more towers.

As well as residences, the country is expending energy in building huge amounts of less necessary things. As Davis pointed out, post-2008 [2], China’s secretive banking sector (secretive like every other sector) might have been carrying half a trillion dollars in “problematic loans, mostly for municipal vanity projects” — and this is socialist Davis quoting the rating agency Moody’s, ten years ago. Construction here in other words is boosted by the same mimicking, flash-conformism that drives everyone to possess the same luxury handbag at once: the municipal equivalent is the swish high rise or the mall, or worse, the ancient urban center mutilated to resemble a mall. There is little restlessness from the people about the appearance of so much awful stuff. For many of the people, these forms are so new that they can’t be readily compared with other things.

Unfortunately for the Chinese, and possibly the world, that country’s planned consumer boom is quickly morphing into a dangerous real-estate bubble. China has caught the Dubai virus and now every city there with more than one million inhabitants (at least 160 at last count) aspires to brand itself with a Rem Koolhaas skyscraper or a destination mega-mall… Despite the reassuring image of omniscient Beijing Mandarins in cool control of the financial system, China actually seems to be functioning like 160 iterations of Boardwalk empire, where big city political bosses and allied private developers are able to forge their own backdoor deals with giant state banks. (Davis, Guardian, July 2011)

[2] ‘Crash Club – what happens when three economies collide,’ Mike Davis, for TomDispatch.com, republished Guardian, Wednesday 27 July 2011.

It all operates on tiers, as well as copying: people are tiered via money, exam results, official titles in jobs or the army, or with raises or bonuses; companies are tiered, and the cities are likewise officially tiered. And yet structural change is rampant. Re-tiering is the manic religion. The difference with the ‘disruption’-obsessed west is the flatness and totality of the tier one occupies, and the way the occupants of each tier recklessly look upwards all at once.

As is well known, advancements for people, and for groups, can happen through showing loyalty. One marks oneself for promotion through obedience and promoting the ‘harmony’ of the working group – even in a disruptive startup. At the same time, one’s group, city, company or school is in competition with others. If one’s home city can’t be expected to become another Shanghai, then it will still aspire to be, and one portion of the skyline will receive the needed surgery. Everyone seems to be looking towards the sky, which is what the architecture forces you to do. Changsha’s aborted ‘Sky City’ project is only an odd example of competitive tower-making because it didn’t go ahead.

In Shanghai, since the late 1980s especially, the process of making more of the city has been made into its own algorithm; the input consists of new babies and foreigners and internal migrants, and the product is more Shanghai. The demarcation of space for future building is imperious. As mentioned above, the delta and inland areas designated part of the planning zone are vast. Within the old city itself, a small number of tiny districts remain in the old, narrow laneway style – places that, admittedly, would have reached an unsanitary degree of crowding if they had to carry a modern population (traditional filth being one of the best kept traditions in those areas of China where real traditions survive).

In Shanghai, some of the intricate old districts are extant. Most are marked for demolition. Smallness and oldness are under threat everywhere. The protestors one most regularly saw outside the Shanghai Higher People’s courthouse, near which I lived, were the old people whose city-center neighborhoods or development zone villages had been pressure-purchased and demolished.

A law student who interned in the justice ministry told me the term existed for neighborhoods inhabited by these elderly development-resisters: ‘Nail units’.

During her internship, she was given the responsibility of dealing with their paperwork, and in some cases had to decide to accept or reject their objections to (effectively) forced communal purchase. According to the constitution, the people own the land (perhaps even the particular people that live on particular plots), so their reluctance receives due, but ultimately symbolic, attention from the justice system.

Whenever one of these street protests gathered at the courthouse in a mass of more than twelve people, they were confined to the far side of the road, and a deployment of double that number of armed police stood opposite them. The guards, wearing faces of resolution, protected the sharkfin-shaped wedge of the courthouse from the infirm, fallen-faced couples, wheezing indignation through cheap loudspeakers from their wheelchairs. Yet, a strange detail to my mind is that the majority of these protests seemed to be about not having received enough money for a forced purchase. “Give us money!” I could hear them shouting on my way home from work.

***

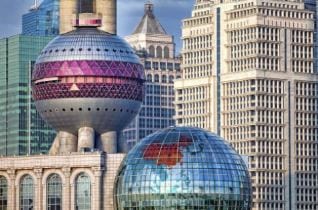

The Bund is the edge of Puxi; the Lujiazui skyline centers on a roundabout on the doorstep of Pudong. The ‘Pudong New Area’ [3] itself extends for endless kilometers east, a floodplain of former fields and villages which is now high-rises, government mini-cities, industrial technology parks and weird gated suburbs of mini-mansions.

[3] The Huang Pu is the main river, itself a distributary of the Yangtze; the suffixes in Pudong and Puxi (the older centre) mean east and west of the river respectively.

In five years I never saw the port, the largest in the world, nor any seashore, having been very dissuaded from even trying to locate the latter by anyone I asked. When I travelled inland by car with friends, whenever I asked if we were still in Shanghai, we were always still there, in the municipality at least. Even when it no longer resembled a city around us, 30-story buildings had a way of appearing like spores in the midst of fields.

Once, meeting an American architect, I learned how the skyscraper follies are made. Part of the process is the foreign talent: the ‘starchitect’ is there for a short trip. He sketches an outline, maybe a remake of a building he’s done before. He leaves his signature.

In all the mimicking and copying of western things, is there a flash forward to the stage of bringing the foreigner into submission, and then on to the related process of destruction, as with the Romans and the Carthaginians? Is it a feint or a dodge or a feebleness? The Chinese, who with justification boast of having borders twice as old as anything else still standing, might not see much meaning in the question.

But why do you copy? Because we are not developed yet.

But when you are developed, what will you do?

One often copies first out of necessity and then out of rivalry, before surpassing one’s model. Rather than performing homage or acting out of inferiority, by bringing western forms into the pageantry of imitation, China could be seen to be building towards the future by saying that the west is part of the past, the vestiges of which should be made rapidly into tourist attractions.

Lu Xun, the early-20th century writer and the greatest modernist, born at the end of the Qing and watching the painful early republican years, often has a quote misattributed to him:

“We Chinese have never looked at foreigners as human beings. We either look up to them as saints or down on them as beasts.”

It turns out that he was quoting an American missionary.

***

In 2015, when I finally got out of Shanghai for Chinese New Year, after many months getting settled, I looked out the window of the train and saw what everyone else had expected.

It was bad weather. Either there was grey soil with pale crop shadows under the mist or smog, or it was apartment stems lifting from the fields, miniature shells and often incomplete, with no one working on them, unlike the ones in the city, with dribbling stains down their sides and no sign of movement anywhere apart from the weather.

Or later – it was the image of the Chinese wilderness from their paintings. Forested hills and mountains with the mist unpeeling from their crests. A different hand painted the mountain tops onto the sky, giving them scooping sides and inaccessible trees that were like drops of nighttime on the cliffs.

No tenderness came from the landscape outside the train, but it did look fascinating. It also had the look of a landscape that other people had inhabited without seeing it as strange. Although it belonged to others, it looked slightly miraculous that it was there at all. It seemed possible one could step into it, as they did, and move through it like them, knowing you would make almost no impression there, the way a worm turns his own little corner of the earth.