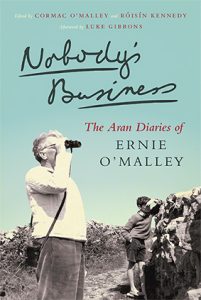

Luke Gibbons on ‘Nobody’s Business’: The Aran Diaries of Ernie O’Malley

An abridged version of Luke Gibbons’ speech at the launch of ‘Nobody’s Business’: The Aran Diaries of Ernie O’Malley edited by Cormac O’Malley and Róisín Kennedy

[…] You could argue that Ernie always kept his cards close to his chest, even when writing his diaries because one of the first things that strikes when reading these, as Róisín mentioned, is the forthright speaking and trenchant observations could not have seen the light of day in their own time. Ernie was taken to court On Another Man’s Wound and he was involved in a liable case. He certainly would have been involved in many a liable case with the content you see in the diaries. As Oscar Wilde once said, ‘I never travel without my diary, one should always have something sensational to read’.

The Aran Diaries were not meant for immediate public consumption, and there were a number of difficulties in making the diaries ready for the public. Someone mentioned O’Malley handwriting, I must say he didn’t make it easy for Dublin Castle. I mean, Dublin Castle must have dreaded finding his papers because of the inscrutable handwriting. There is very little of the private self in the diaries in terms of introspection or soul-searching. Instead, O’Malley immersed himself in the Irish people and the Irish countryside to find himself.

O’Malley includes the way of telling in the very enunciation of stories, bad grammar, hesitations, humming and hawing; the perception that that is where the true lies, it’s what’s not being said as well as what is being said. Hence, The voice in these diaries is more assured looking out than looking in. Looking, as Róisín points out, is a key activity in the diaries as O’Malley brings a paint er’s eye to everything he looks at but with a hand touch of the romantic. The romantic seeks fusion with the community.

er’s eye to everything he looks at but with a hand touch of the romantic. The romantic seeks fusion with the community.

However, O’Malley had no illusions about going native. His Irish wasn’t good enough to go native with the islanders, he had no illusion about being one of the people in that sense. He said he had noticed great gaps in the walls on The Aran Islands and that gaps let people in but they also let people out.

One of the most rewarding aspects of the journals is the way the people O’Malley speaks to come alive including the artist Elizabeth Rivers and Charles Lamb and Pat Mullan. Though alive to the sea and the landscape it was the people who concerned O’Malley the most, and how they made ends meet at the edge of modernity. He was constantly thinking of ways to modernize fishing, agriculture, architecture, crafts and textiles but not in ways that cut people off from place. Constantly modernizing, but not at the cost of connection to place. One might not immediately associate Ernie O’Malley, the guerilla fighter with an interest in knitting but he was against patterns being lifted from Aran to be used for machine-made products being sold in Dublin  . So, in fact this had already happened in the 1940s, machine-based patterns lifting from the original Aran. O’Malley, for all his interest in technology, hated that.

. So, in fact this had already happened in the 1940s, machine-based patterns lifting from the original Aran. O’Malley, for all his interest in technology, hated that.

O’Malley’s war experience haunted him for the rest of his life. And comes back to him in the most unexpected ways. Cramped with his son Cormac in a small room on The Aran Islands, his feelings of discomfort are tempered by warm memories. This is what he says, ‘at first glance one thinks this is an impossible situation. where will I hang my clothes? Where will place my books? My dirty clothes? Jail has already solved many things in my mind.’ Once you were in Kilmainham you put up with a lot afterwards. O’Malley was trying to solve things left over in his mind from time in jail. For him, every day counted as if it is to be the last day. This intense appreciation of what it was to be alive at all, to have time on one’s hands when one had faced execution that comes across most in the diaries and that makes reading them such an enriching experience. I’m so glad Cormac put his hands on the diaries

Getting a second chance and third chance makes him alert to everything and that’s how he brings the painter’s eye and the writer’s voice to bear on even the most common places