Charles Lysaght on Adrian Kenny’s Before the Wax Hardened

An abridged version of Charles Lysaght’s speech at Adrian Kenny’s launch.

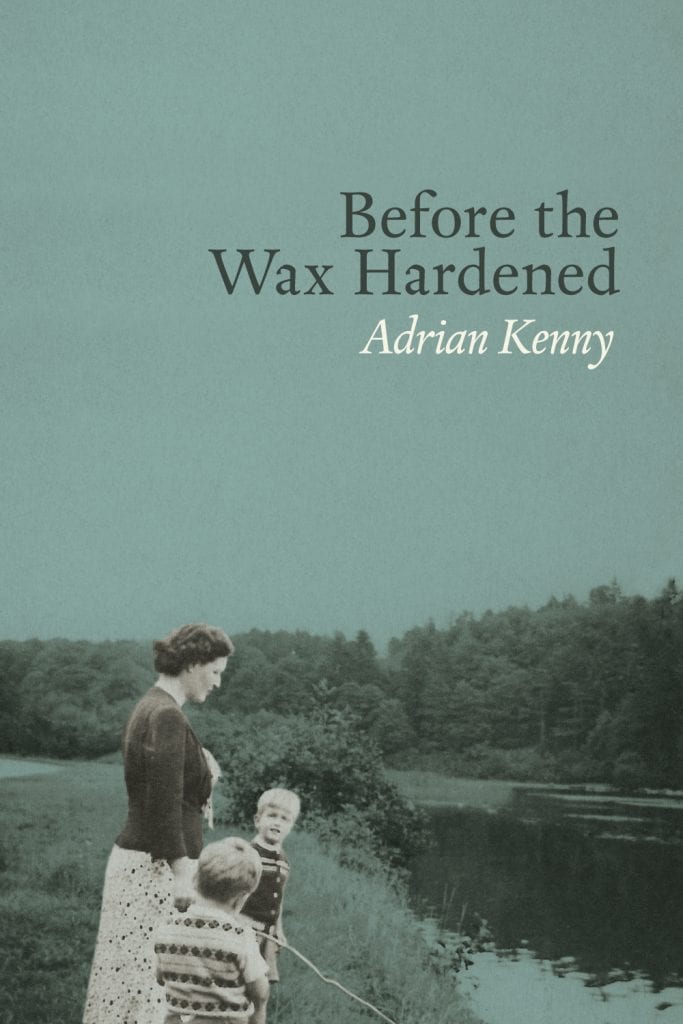

I am honoured to be invited to launch this reissue by Lilliput Press (with relatively minor additions) of a book entitled Before the Wax Hardened written by my friend Adrian Kenny and first published a quarter of a century ago. Of its many fine features the finest is its honesty. It is an intrusion of honesty into a notoriously dishonest genre of literature – autobiography. Autobiographies or memoirs are so often exercises in public relations written by the successful and would-be successful painting a sympathetic picture of themselves with a few discreet boasts. It may be that most people are happy not to have the whole truth, especially about themselves.

A pleasant existence, the accumulation of wealth and achievement of position come higher in the priorities of normal people – to use a term that finds a place in Adrian’s book.

In literature the novel or short story has long been the vehicle for conveying the reality of life and lives. Adrian tried this with his novel The Feast of Michaelmas published in 1978 and a collection of short stories published in 1983. They did not satisfy his literary soul. So it was that in 1991 he produced the first edition of this book which is best described as autobiography written in the style of a novel or a short story, a genre of which Adrian is also a past master — as you will know from his Portobello Notebook published in 2012. He brings to it the keen observation of the novelist and a deadly ear for dialogue. He is almost ruthless in exposing his own foibles and failings and things most people would keep secret about themselves – for fear of blunting sales I will not elaborate on this.

He is piercing in his vision into those he encounters. Adrian and I have in common that we were at school in Gonzaga; while I was five classes ahead we entered the school on the same day in 1953. Gonzaga is now much the same as a lot of other Dublin secondary schools. But in those days we thought of ourselves as special. The vast majority of the masters were Jesuits, whom Adrian recalls as exuding calm – coldness, I would have said. We followed a special curriculum uncramped by the requirements of State exams based on the traditional Jesuit ratio studiorum. The founder and head of the school was the Jesuit O’Conor Don, Father Charles O’Conor, descendant of the ancient kings of Connacht. Alone of the characters in Adrian’s book is given his real name. The grandeur of Father O’Conor rubbed off a bit on the rest of us. The bread man in the book who says ‘you’re meant to be gentlemen in there’ may have voiced a view/perception held more widely.

There was a remarkable English master called Father Joe Veale — Father Wilmot in this book – who spotted Adrian’s talent and used to read his essays out in class. The sharp depiction of Joe Veale and of the other masters as well as many of the boys — not me mercifully – means that the book does for Gonzaga what Joyce’s Portrait did for Belvedere. Like Joyce’s book its truthfulness has given offence and the book is not as much appreciated in the old school as it should be. In the fullness of time that will change. It will be regarded not only as a literary jewel but as an invaluable record. Those mentioned in this book when long dead will be remembered as characters in Before the Wax Hardened and books will be written by scholars as to their real identity and the forgotten details of their lives explored. If there are still Jesuits, one of them might even emulate what Father Bruce Bradley did with Joyce and write up Adrian for a future Dictionary of Irish Biography as their greatest alumnus. Another link with The Portrait is the quality of the writing—simple and subtle yet powerful and atmospheric. Like Joyce, Adrian is not a page turner. But his writing passes the crucial test of being better on a second or third reading than a first superficial one.

Of course Gonzaga is not all that is depicted by Adrian in this account of his young life up to the time he abandons the study of history having spent a year at the University of Tennessee working under an uncongenial professor who had the hardihood to tell him he should have taken a course in ‘English for Foreigners’. The new edition has added something on Adrian’s American sojourn. There is his family. His parents both came from small farms in the west of Ireland. His father, a Mayo man, worked himself to the bone, overcame alcoholism and built up a thriving string of shoe shops in Dublin. Success and ambition took their toll on him making him stressed and unsympathetic, even repressive, as a father, well able to clip ears and wield the cane [and exhibiting an anti-semitism not uncommon at the time]. His finer qualities are not so apparent in this book as in Adrian’s later memoir The Family Business published in the last year of the old century which led to Adrian being admitted to the select, if now threatened, company of the Aosdána .

It is a subjective and selective memoir, not aiming to be a comprehensive autobiography. Adrian’s ear for dialogue and uncanny recall enable him to create some wonderful set pieces in the book. I love the account of the retired teacher with a grand accent who takes it upon herself to give Adrian and his brother a lesson in history, geography and Irish rolled into one on their train journey to Mayo. ‘By the time we reached Athlone’, Adrian remarks with his wry wit, ‘I was as tired as if we had walked.’ Adrian Kenny is to be congratulated for combining an account of his own personal odyssey with a penetrating insight into the Ireland in which he grew up.

Charles Lysaght, May 2017