Form, Flann, and Lyric Poems: 5 Questions for Aidan Mathews

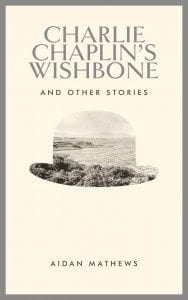

Aidan Mathews’ latest short story collection, Charlie Chaplin’s Wishbone and Other Stories, really has something for everyone. The author displays his flair for delving into the minds of an eclectic group of characters – from ‘A Woman from Walkinstown‘, musing on the decline of her name, Mary, to the teenage girl spending a Saturday afternoon with her separated father. Decades pass within its pages – the imprisonment of Anton Artaud in 1937 gives way to the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, while stories set in our time make substantial appearances.

In light of this impressive range, we pick Aidan’s brains about the nature of form, the helping hands of Puffin paperbacks, and the short story masters you should have on your bookshelf …

In light of this impressive range, we pick Aidan’s brains about the nature of form, the helping hands of Puffin paperbacks, and the short story masters you should have on your bookshelf …

1) This collection has been described as postmodern, with echoes of Flann O’Brien in the espadrille episode in ‘In The Form of Fiction.’ How would you describe the collection? Is a subversion of the genre something you sought to do consciously, or do you think that the short story form lends itself well to subversion?

Flann O’Brien died in my father’s care in Mercer’s Hospital, and his brother Kevin taught me Latin in UCD; but, apart from the Peacock production of At Swim Two Birds in, I think, 1970, and my later purchase of the Penguin edition with its gorgeous Jack B. Yeats cover, the connection is slight and rather sad, because so many of the marvelous mid-century Irish writers in my parents’ bookshelves, master humorists included, seemed afflicted by alcoholic melancholy and self-loathing.

2) Do you feel more comfortable with the short story form than with the novel?

I may/must do, because I’ve only ever managed one novel. Muesli at Midnight was an attempt at an anti-novel in the Tristram Shandy tradition. I do love large narrative fictions, but I’ve never been able wholly to believe in their presuppositions. Those 19nth century notions of the self and of society, of character and circumstance, and of the dialectical interaction of the two to present plot-line, are as artificial, and therefore as simplistic, as the mythologies that European literature replaced after the Reformation.

On the other hand, I don’t really write short stories as such. I write long short stories mostly, since long short stories – or the novella, if you wish to be posh – dominated fashion when I was an undergraduate long ago. Brevity bulked large in the 1970s, in the last little while before the cut-and-paste of Microsoft ease ousted the difficult cut-and-thrust of pencil-marks on perforated type-script.

3) You’ve written novels, poetry, plays, short fiction – do you enjoy exploring these different mediums, and which is your favourite (if you can choose)?

I’ve more or less enjoyed every foray into form, except for the creativity-by-committee that screen-writers have to endure; but, because liturgy was my first experience of the wise Eros of language (I served the morning mass in Latin as a prep-school pupil), I am fondest of the lyric poem, which chills the most ordinary words with an acapella acoustic.