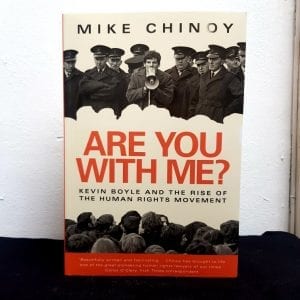

Extract: Are You With Me? Kevin Boyle and the Rise of the Human Rights Movement

Kevin Boyle played a major role over many years in seeking a peaceful resolution to the conflict in Northern Ireland. One previously unknown initiative involved his effort, with fellow lawyer Francis Keenan, to use the European Commission on Human Rights as a mechanism to seek a negotiated solution to the 1981 IRA hunger strike. That effort is the subject of this excerpt from Are You With Me? Kevin Boyle and the Rise of the Human Rights Movement by former CNN correspondent Mike Chinoy.

Kevin Boyle watched the hunger strike crisis with growing dismay. Sympathetic to the predicament of the prisoners, and disgusted by what he and many others saw as Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s intransigence, he was deeply concerned that her behaviour was going to drive more people into the arms of the Provisionals.

Almost lost amid the worsening crisis was the fact that in mid-May 1983, the European Commission on Human Rights had decided that two remaining elements of an original application Boyle and Francis Keenan had filed on behalf of Thomas McFeeley and three other prisoners who had participated in the first IRA hunger strike in 1980 were admissible. The Commission informed the British government that it was welcome to submit whatever proposals it wished as part of a process known as a ‘friendly settlement’, in which the Commission would offer its services to both sides in the hope the two parties could resolve the issue. The Commission also proposed what were in effect ‘proximity talks’, inviting the government to send representatives for an informal meeting, while asking Boyle and Keenan to travel to Strasbourg as well. ‘A move for a friendly settlement would be a form of pressure on both sides,’ Keenan recalled. ‘It would especially put pressure on the British to be more reasonable.’

Thatcher remained adamant that she was not interested in using the Commission as a channel to negotiate with the IRA, but she did agree to respond to the Commission’s invitation to send representatives to Strasbourg. She wasn’t alone, however, in her scepticism. Although Keenan remains uncertain about the precise date, he recalled being summoned with Boyle to a meeting with the Provisionals’ leader, Gerry Adams, under somewhat melodramatic circumstances. The two men had been driving to the Maze prison to see Thomas McFeeley when a car raced up and signalled for them to pull over. The driver was Pat Finucane, the lawyer who had represented Bobby Sands and was now advising the Provisional Sinn Féin leadership. ‘He told us we were not to go to the Maze,’ Keenan said, ‘and that Mr Adams wanted to see us.’ Sitting in their car by the side of the road, Keenan and Boyle discussed what they should do. Keenan felt strongly they should ignore Adams. ‘If we gave in at that stage,’ he remembered telling Boyle, ‘we were effectively saying to our clients that we were not acting totally on your behalf. We are acting on your behalf only insofar as Adams permits us to do so.’ ‘Look, Adams is in control of the situation,’ Boyle responded, ‘and you have to talk to him. We have to go in and make our point here.’

Keenan eventually reluctantly agreed, and the two men turned around and drove to Sinn Féin’s heavily fortified headquarters on the Falls Road in Belfast. Adams, accompanied by an aide, was civil but dismissive. According to Keenan, ‘he said we were more or less giving false hopes to the prisoners’ that the Commission could actually do anything. ‘The clear impression given by Adams was that we were very good boys but that we were out of our depth and totally naive.’ The meeting was inconclusive, and the two men came away with the impression that Adams wasn’t seriously interested in a settlement. As they left, Boyle turned to Keenan and said, ‘You’re right. We should just ignore Adams.’ For Boyle, it was an unsettling experience to meet with someone who, in his view, had ‘endorsed killing. I didn’t find it easy to talk to him,’ he told an interviewer years later.

With no end in sight to the hunger strike and a mounting death toll both in prison and on the streets, Boyle and Keenan travelled to Strasbourg to explore whether the McFeeley case offered any hope of breaking the deadlock. On 3 June Michael O’Boyle and Hans Kruger of the Commission secretariat held separate talks with Boyle and Keenan on the one hand, and a group of British officials and legal experts on the other. In deference to British sensitivities, the Commission officials made clear that these were not negotiations on a friendly settlement, but rather exploratory discussions – talks about talks – on the possibility of the Commission’s involvement. The British position, however, remained unyielding. The day ended with no accord.

In early July, Garret FitzGerald became Ireland’s new prime minister. FitzGerald was anxious to find a way to end the hunger strike before the Provisionals reaped even more political benefits. Soon after he took office, Boyle and Keenan arranged a private meeting, and told FitzGerald that it might yet be possible for the Commission to play a constructive role.

In the meantime, in Strasbourg, Commission official Michael O’Boyle was working what was dubbed a ‘blueprint’ – a new set of specifics that could be discussed if the ‘friendly settlement’ mechanism were activated. As he recalled, the blueprint was ‘a document setting out how the remaining McFeeley complaints could be used as a springboard for settling the wider issues at the root of the claim for “special category” status – the requirement to wear prison garb and work and, and the right to correspond with the outside world. ‘It could have provided an elegant way of climbing down without losing face.’

In early September a second meeting was finally arranged. Boyle and Keenan returned to Strasbourg, along with a team of British officials and legal advisors. But, as Michael O’Boyle recalled, at the last minute the British had been given instructions ‘not to engage with the Commission or Kevin or Francis’. Boyle and Keenan were told the British officials were actually in a nearby room at Commission headquarters, but it fell to O’Boyle to break the news to the two men that ‘the process was aborted and no meeting would take place. They were very upset; I suppose because of what the future had in store.’

The reason for the abrupt turnaround was Margaret Thatcher, who had had an eleventh-hour change of heart and, in O’Boyle’s words, ‘pulled the plug’. It was hardly a surprise. Thatcher had been wary of being drawn into such a process for months. ‘She obviously wanted to make it absolutely clear that the time for ambiguity was over and that there would be no discussions in whatever form,’ O’Boyle noted. As Boyle told a reporter: ‘What is wrong is the British Prime Minister is simply not prepared to move the little distance necessary to settle it.’ To O’Boyle, a Belfast native, ‘an important historical opportunity was missed to stop the hunger strikes in their tracks. It was a great pity.’